When I last left you, we had a big day in Khajuraho, touring some super sexy temples, and experiencing some amazing Ayurvedic massage therapy.

The next morning, we were up at dark o’thirty, for an (optional) jeep safari tour in a national park near Khajuraho, where there was a chance that we might see an Indian tiger or two, in the wild. Later that morning, we were scheduled to fly to Varanasi, our last stop in India. After that, we would be flying to Khatmandu in Nepal, for a quickie tour of the broken city, before heading home. So yes, this epic serial trip report is almost a wrap.

If you missed any of the previous chapters of this blog series, you can find them here:

Chapter 1 – Just Say No to Delhi Belly

Chapter 2 – Walking in Ghandi’s Footsteps in Delhi

Chapter 3 – Worlds Colliding in Jaipur

Chapter 4 – Agra

Chapter 5 – Sexy Temples and Buck Naked Backrubs in the Indian Outback

I have been stalling a bit about writing this next chapter about Varanasi. It’s a difficult place to describe.

Bonnie, our trip leader, really hyped Varanasi as the culmination and highlight of our journey in India. It is the spiritual capital of India, she said, the city that the Hindus say is for learning, and burning.

Varanasi is located on the banks of the Ganges River. For Hindus, the Ganges is a sacred, mystical river that flows from its source way up in the Himalayas, for 2500 km, before it empties into the Indian Ocean at Bangladesh, in the Bay of Bengal. Its flood plain is quite large, and the lands near it are apparently super fertile. To learn more about the Ganges River, I highly recommend watching the Wildest India – Ganges: River of Life documentary on Netflix. In fact, the whole Wildest India series is pretty darn wonderful.

There is some science out there that suggests that the Ganges has some very special bacteria in it – beneficial bacteria that consume other, nasty micro-critters. I wasn’t willing to drink it to prove or debunk the myth 😉

At Varanasi, which is about half way along the Ganges’ long course to the sea (and as close to heaven as you can get on Earth, according to the Hindus), thousands and thousands of bodies are burned on the banks of the river, 24/7/365.

Varanasi is the place where Hindus, if they have any means at all, want to die and be cremated. And the cremations are not done in tidy, discreet, environmentally sensitive, anonymous-looking buildings – not so much – the bodies are cremated in open air, on crackling wood fires, on concrete platforms, next to the river. And then the smouldering remains are raked down to the water’s edge, where the river sooner or later reclaims them. The bodies burn for just a few hours before the leftovers are relocated to the river, and then a new fire is built, and another body brought down for its smokey, ritual-laden dispatch.

You could see this as a beautiful good-bye: the body of a loved one, brought to Varanasi to be laid to rest, carried respectfully down to the river and dipped in its sacred waters, then laid out carefully on the concrete steps of the ghat to dry for a bit, while the fire is being laid. Only male mourners are at these cremations, and attend to the body and the pyre; the women are at home, grieving in private. Wood and straw are stacked up to create a rudimentary cradle on the concrete. And then the shrouded body is laid in the temporary tinder box, covered with more straw, and then after some prayers, they light it up. With dry wood and straw as fuel, the fire gets going quite briskly. After an hour or so, the lead mourner (often the eldest son), takes a large bamboo pole and taps the skull to break it, and in doing so releases its spirit to the heavens.

Or you could see this as pretty macabre: dead bodies laying around on the open steps. Dogs and cows rooting through the filthy piles of ashes and bones along the water’s edge, eerily lit by the light of the numerous pyres. A worker of the lowest caste (Sudra), sifting through the mucky remains to retrieve nuggets of melted gold teeth and jewelry that adorn the cadavers when they are burned. Or it could be the phlock of a human wielding a bamboo pole smashing the skull of a burning body to break it open like a well-baked coconut that pretty much tips you over the edge.

Truthfully, I really wanted it to be beautiful and awe-inspiring and spiritual. But I have to admit that instead, it was all a bit hell-like to me. I think it didn’t help that we had awoken super early that day, had a big adventure in the peaceful jungle, flown to Varanasi, then commuted by bicycle rickshaw and foot through the stress-inducing, crazy, cacophonous crowds in the inner city, then motored down an evidently very polluted river to the burning ghat, at twilight, where we floated just off the shore – close enough to hear the many funeral fires crackling and burning, and to watch the scene unravel…

Anyhoo, first, back to the safari. As I mentioned above, there was no guarantee that we would see tigers in the wild, but the ladies decided it would be awesome to take in some natural scenery in India, especially after the massive brush with humanity that we had experienced over the past week in places like Delhi, Jaipur and Agra.

Panna National Park in the province of Madhya Pradesh is the largest remaining natural reserve in this part of India. Much of India has been cleared for agricultural purposes, and the area around Khajuraho is no exception.

At the moment, the Panna Reserve, which covers over 200 square miles, indicates that it has a population of 14 tigers. In 2009, all of the tigers of Panna Park reserve were poached (rumour has it that park officials were in collusion with this despicable act), so the tigers now populating this area are imported from other tiger reserves in India, and their resultant offspring. Good thing that tigers are willing to relocate I guess.

The reserve is quite lovely – sort of an arid forest, at least in the dry season when we were visiting. The trees appeared to be quite stunted and gnarly, and the colours were very dusty and muted. Despite the dearth of tigers, we did see quite a lot of wildlife, including many deer – apparently the main menu for the big, carnivorous cats.

Be wery wery qwiet (that was for the Elmer Fudd fans out there). Here, we are stopped and waiting for tigers. Sadly, none were to be seen on this day.

The tigers have radio collars on them, so the rangers have an idea where they might be in the reserve – but they had apparently had a kill early in the morning that day, so were probably sleeping it off in the shade somewhere out of sight.

These deer come to the large, man-made water pond to drink and frolic. It was cool seeing the deer hopping and splashing their way across the milky water to exit on the other side, and then fade into the woods.

Back on the road, in the countryside near Khajuraho.

Back on the bus, headed for the airport at Khajuraho. It looks like they’ve got a brand spanking new terminal just about ready to open in this little town. I am wondering if this means that this lovely, peaceful part of India is about to become very touristed as well.

Landing in Varanasi less than an hour later, we did a drive by luggage dump at the hotel, and then immediately headed into the city.

Not sure whether these things are decorations for weddings, or perhaps funerals, but the balancing act is admirable.

A sea of humanity in the core of the city. This picture can not possibly illustrate the level of noise, so you’ll just have to believe me when I tell you it was deafening.

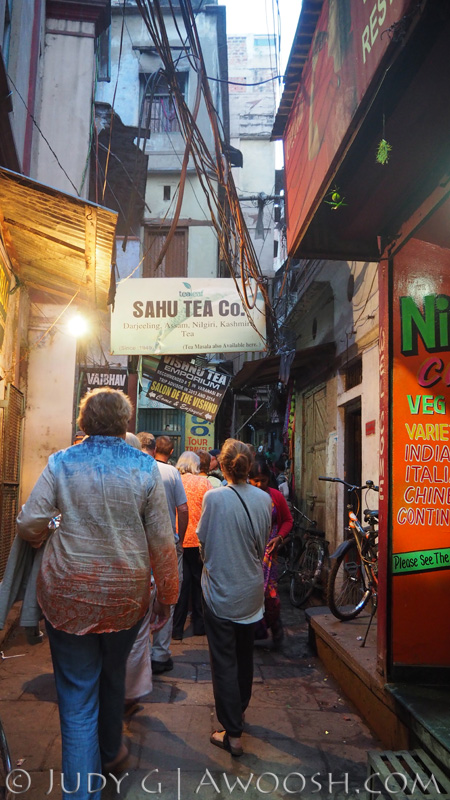

Walking in the narrow alleys of the very old part of Varanasi. Beware the cow pies. We were told there are something like 30,000 cows wandering the streets of Varanasi. That is a load of sh*t!

This is the largest burning ghat in Varanasi. At any given time, there are at least 10-12 cremations going on.

A closer in view of the hellish happenings. I zoomed my lens to take this picture. Once we floated in closer to shore, we were asked to not take pictures, out of respect.

Each of us was given a lit little paper votive candle to release on the river. With it goes a prayer, or a wish, and sadly yet more garbage…

This is the scene of the nightly Hindu Aarti fire ceremony, on a ghat in Varanasi. Thousands and thousands of people attend to worship, and to hear the devotional music.

New day, new perception. Seeing the sun rise serenely over the Ganges contrasted strongly with the craziness of the previous evening, and was a beautiful experience.

Priests along the ghat perform ceremonial rituals as the sun rises in the east, across the sacred river.

All Hindus hope to make at least one pilgrimage to Varanasi in their lifetime. Part of the ritual is the dunking in the river at dawn. This is as much skin as you’ll see in India. Note the women in the background are wearing swimming saris.

People bathe in, and drink the Ganges. The bathing is a sort of self-Baptism, done at sunrise – the washing away of sin – the waters are said to have healing properties. Ditto the drinking.

Pilgrims come from all over India to Varanasi, not just for dying and cremation, but also to partake of the river, at this most sacred of locations. And they take home big plastic containers of Ganges water for rituals, which is said to keep for a lifetime without spoiling.

There is definitely a lot of commerce around dying in Varanasi. The guy that owns the big burning ghat, even though he comes from the lowest caste in India (who are the people who deal with death and bodies, amongst other perceived unsavoury occupations), is the richest guy in town, and he lives in a palace on the river. The ghat has been his family’s business for many generations.

Hindus believe that the cremation must happen within six hours of death, and many families bring their elderly or terminally ill relatives to Varanasi to die, especially if they live more than a couple of hundred kilometres away.

These days, a cremation on the ghats of the Ganges runs about the equivalent of US$500 – a fortune for most Indians. For those who can’t afford a Varanasi cremation, or live too far from Varanasi to contemplate bringing their near or newly dead relative there, cremation can be done closer to home, and then the ashes brought to Varanasi, to be released into the river as part of the pilgrimage.

It is a crazy place – so different from the way that the western world deals with death and dying. But death in Varanasi is an ancient tradition, and for millions of people in India, Varanasi is a place of supreme spiritual importance.

Looking south, down the river. In the distance is a more modern indoor, electrically powered crematorium. Although more environmentally friendly than the open burning, Hindus are slow to embrace this new technology. The air pollution generated by the wood burning pyres, and the massive amount of wood consumed to make the fires would appear to be non-sustainable.

Looking north, up the river. Interestingly, while this west bank of the river is super developed and populated, the opposite (east) bank looks to be pretty much barren and devoid of humanity. Also of note, the burning ghat is located just upstream from the bathing ghats.

One of the more popular ghats where the pilgrims and devout locals come to immerse themselves in the water in the morning. This was where the Aarti ceremonies are held in the evening.

A few parting shots from Varanasi:

Next up: our final stop on the tour – Kathmandu, Nepal.