Nemunyak Community Conservancy — Sarara Camp

Once again my words and photos really can’t do this experience justice.

Sarara Camp is located in a wide valley, with epic views from its rocky perch on the flank of a precipitous mountain, all the way across to the scenic Mathews range rising out of the plain on the far side. The land and rocky formations are mostly reddish — and that red oxide tinged soil is important in the rites and rituals of the local tribe — the Samburu. Trees, bushes, grasslands and sandy river flats make up the terrain in the wide valley, which is cut through with rutty, dusty roads. Animals — both domestic and wild, roam freely (there are no fences anywhere), and they all somehow, for the most part, peacefully co-exist.

Sarara Camp, as well as Sarara Treehouses, Reteti House and Sarara Wilderness mobile camp, are all under the fine leadership of Jeremy Bastard (a bit of an unfortunate name – he sure seems like a super nice guy ;^) and his partner Katie Rowe. Jeremy, a fourth generation Kenyan, spent a lot of time in the area as a child, with his family, and they forged deep bonds with the Samburu.

In 1995, a vision was realized by Samburu elders in creating the 850,000 acre Nemunyak Community Conservancy — as a way of trying to halt the decimation of many wild species in the area due to over-hunting and rampant poaching. The hope was to create an environment that would support the repopulation of these threatened species over time. Out of that, an eco tourism partnership between the Samburu and the Bastard family evolved, and Sarara Camp was built, in 1997.

Sarara Camp, the newer camps named above, the Sarara Foundation, and the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary have all been created as part of an inspirational and sustainable model of social enterprise. Katie & Jeremy explained that it all belongs to the Samburu, and that they manage the lodges for them. 60% of the revenues from the camps is returned directly to the Samburu community through education, health care, conservation protection, and other aid. The remainder is spent on camp staff salaries, provisions, upkeep etc.

The non-profit Reteti Elephant Sanctuary, which directly employs 120 Samburu, also provides empowering income to 1200+ Samburu women who work to supply the large volume of goat’s milk that is needed to feed the young animal orphans. The camps themselves are also key employers in the area, paying wages and providing health benefits for their employees, who in turn, each help to financially support the villages from which they came.

Sarara Camp has 6 two person cabin tents, and one two bedroom family unit. The tents are lovely and very specious – with thatched roofs constructed over them, huge mesh windows looking out over the gorgeous view, and they are all privately situated. They have both indoor and outdoor sink & toilet facilities, a private deck, and an outdoor shower. Nothing like being in the altogether in the shower and having a wild giraffe pop his or her head over the rim to say howdy ;^)

The cabin tents are spread out along the ridge in two layers, with the furthest being a couple of minutes walk away over an up & down sandy path from the main lodge, on which giraffes occasionally stood sentry during out stay, and on one memorable night, a family of elephants came right into the camp to visit.

The main lodge is a lovely building, with a thatched roof covering a comfy and spacious seating area, and with the bar just a short stagger away. Then it’s up a few steps to the dining area. Zazous (hornbill birds) swoop through the open air building, giraffes ramble along the sandy paths right outside, naughty vervet monkeys squabble and chase each other through adjacent trees.

From the deck, or the beanbag chairs on the rocks below, you can sit and lazily watch the animals coming to the watering hole below, which is fed by a natural spring, around which the lodge was planned. Elephants, giraffes, warthogs, baboons, zebras, assorted exotic birds — no need to head out on a bumpy game drive, just sit ye down right there and watch the parade.

There is also a very beautiful infinity edged pool below the living area deck – the sloping bottom is of naturally occurring site rock, and so basically the pool has been created by damming the natural spring over the stone bottom, and then the spring flows through it to the watering holes below.

In addition to the aforementioned Mr Toad’s wild ride game drives, Sarara offers walking safaris with their naturalist guides. They also offer horseback safari for experienced riders (at extra cost). Mr G and I did all three, and greatly enjoyed them all. Daniel was a great guide – very knowledgeable about fauna and flora in the area, and he shared a wealth of knowledge about Samburu lore and folk medicine. And GPS was always along too — he’s the dude wearing the fatigues and carrying the bigass gun. He’s an interesting story — previously he was a deadly accurate (spear) hunter who was responsible for the death of many animals in the valley, prior to the Conservancy being formed. In a beautiful pivot, he is now employed to protect people, and animals.

Our late afternoon ride with Katie Rowe and two of her Samburu guides was lovely. The horses are beautifully cared for and seem to thrive there — well, except the one that she told us got taken by a lion! =8^O. I will admit it was a bit surreal to be riding through the bush, with a couple of Samburu dudes along for the adventure, never knowing what wild critter might be just around the corner. In the same area, on vehicle game drives, we had seen a huge journey of reticulated giraffes (we lost count at 40!), elephants, zebras. ostriches, warthogs, and a flock of ever-confused birds-of-little-brain Vulturine guineafowl. Daniel had said he had seen a leopard in a tree in the area just days before…

Sarara isn’t really about traditional African safari go-till-you-drop game drives. Instead it is more of a place for total relaxation and immersion, in a remote, unspoiled valley, with an aboriginally led land conservancy and a captivating culture to learn about – the Samburu.

In-room massage is available (they don’t have a dedicated spa space), and there is a boutique on site that offers beautiful things made by local artisans.

An opportunity was offered to watch the local blacksmiths forging metal pieces, and everyone who attended had a custom bracelet made for them.

All in all, the food, the hospitality and the excursions were outstanding at Sarara.

Samburu Land

The Samburu people and their culture are fascinating — in many ways they seem anachronistic — a civilization that time has forgotten — which is quite astonishing in the hyper-digital 21st century. This is in part due to the nomadic pastoralist nature of their existence, which means most move their animals and their rudimentary villages as needed to better grazing grounds. Only the mountain dwelling bee keeping Samburu remain in static villages. I believe it is also partly due to the remoteness of this area of Kenya, far from the big cities, and the Samburu’s very strong pride in their heritage that has allowed them to continue in their traditional ways.

During our four days at Sarara, the staff of Sarara Camp, who are almost all Samburu, welcomed us like family, and openly shared many stories and insights into their culture. Robert, the camp manager, or Michael & Ann, assistant managers, would often join us for meals, and would regale us with fascinating stories about the Samburu.

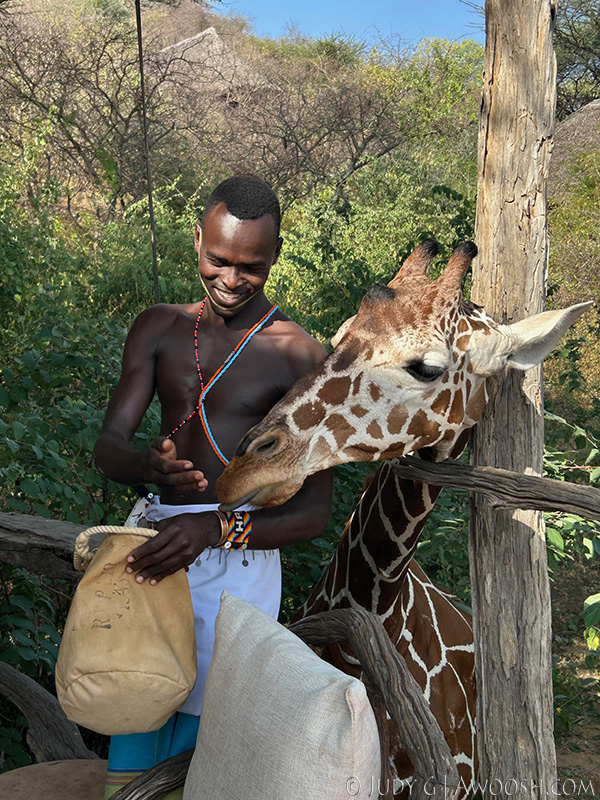

The Samburu people are fiercely proud, dress in wildly colourful clothing, and are beautifully adorned with stunning beadwork. Eligible young Samburu men wear cock-a-doodle head dresses to attract the ladies. Most everyone wears some sort of wrap skirt/shuka with little to no covering above the waist, although brightly coloured plaid blankets worn as wrap around shawls are also common apparel, especially for the elders. And did I mention the beads? The beads are not just for decoration – they also signal all sorts of social cues – betrothed, married, how many wives (the Samburu men are polygamous), whether a teenaged boy has been circumcised, how many sons a mother has, etc, etc.

The Samburu people, who are believed to be a breakout sect of the Maasai (their much better known cousins), and who claim to be a “lost tribe of Israel”, have populated this large area for what is thought to be 6 or 7 centuries. So far only small (but no doubt ultimately significant) changes to their culture have seemed to have occurred over the centuries. ‘Chinese gazelles’ (low cc, inexpensive dirt bikes) and mobile phones have finally arrived, as of the last five years or so. The times, they are no doubt now a-changing, even in Samburu land, but a very strong sense of community, values, and one’s place in the world will hopefully help them to stay the course, at least for the most part.

Theirs is an oral tradition – this is how their history, medicines, rituals etc have been traditionally communicated.

I had never heard of the Samburu before our trip, although I feel sure that at one time or another there must have been a feature in National Geographic about them. The only accurate book written about them is Samburu, by Nigel Pavitt. He spent many years in the area, and in doing so, earned the trust of the Samburu, and with their agreement, he documented some of their people and their rituals. We were explicitly asked to not photograph Samburu people, nor their domestic animals, as it is their belief that photographs steal the soul. Any photos of Samburu that appear in this photo essay are of employees of Sarara Camp and Reteti Elephant Sanctuary, who do permit their photos to be taken. We bought a copy of Pavitt’s book at the camp for its beautiful photographs, but immersing myself in his detailed explanations of complex rituals and social nuances has allowed me to learn much more about what we saw and experienced.

We heard many stories and explanations of Samburu culture — too many to share here — but I know that we all left with sincere admiration for their incredibly strong sense of community, respect for their elders, connection with the natural world, and apparent lack of desire for most modern conveniences. But truthfully, we were also challenged by some of their more archaic beliefs — particularly the patriarchal practices of arranged marriages (where the women have no say in who they will wed; the weddings are typically transactional, and the brides are typically very young and are often wed to much older men), polygamy (men can have numerous wives), the circumcision rituals around both teenaged males and females, and the usual practice of not sending kids to school — instead, most are tasked, starting at a very young age, with tending the family’s herds of cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys and camels. Animals are currency to the Samburu. Young boys are routinely sent out into the bush to fend for themselves for long periods of time, far from their villages. Girls stay closer to home and tend the goats and sheep. ’Naughty’ boys and girls are those that are not overly attentive to the animals, losing some to predators etc, and their punishment is being sent to school!

Picture this in your mind: On the day we arrived, we were told that there was to be a traditional Samburu wedding in a nearby village, and that we were most definitely invited to attend. A wedding was apparently not usual for the dry time of year when we visited; typically most weddings occur during the wet season. It was decided that our group should offer the bride and groom a gift, and a live goat was suggested as being the appropriate thing. Alrighty then.

We all piled into two vehicles and drove the adventurous route to the village, which included fording rocky streams and avoiding herds of cattle and goats being shepherded along by young boys and girls on what can only generously be called roads. As we pulled into the outskirts of a traditional village on a hot and beautiful late afternoon, things were definitely already underway. We found out later that Samburu wedding rituals and celebrations last for three days!

A clan of buff bare-chested young men — warriors — who were all beautifully decorated with colourful skirt wraps (shukas) and ornately beaded bracelets, anklets, necklaces and headgear, were gathered on the dusty flats outside the modest village circle beyond. Many of these guys wore ornate long braids down their backs, coloured red with the iron oxide mud made from the soil, faces painted, carrying long spears, with daggers and clubs tucked into their beaded belts. And then they pronked. Usually two at a time would pair off, and begin leaping vertically into the air, higher than you would think possible from a standing position, and seeming to not use their knees for propulsion, only their ankles. It was clearly a full on show off, but not for us, for themselves, and for the young ladies gathered on the sidelines nearby. Guttural chanting was the soundtrack. It was truly a scene — a spectacle that none of us will ever forget.

And then, one of the young men appeared to have an epileptic fit, and then another, and then a third. Totally rigid, limbs quaking, wild eyes. They were each picked up like a plank by a few of their friends, and carried off to the side to recover in the shade. We were all aghast — was this epilepsy? Or heat stroke? (which would have been totally understandable given how hot it was, and how much energy they were exerting — and that there was no apparent hydration happening). But no, our Samburu guides Daniel and Pius assured us, this is normal — these young men are overcome with emotion. One explanation was that it was possible that these boys might have been romantically involved with the young bride, or were her brothers, and were devastated that she was being married off and would leave their village to live with her husband’s family (including his other wives).

The young ladies watched covertly as the sea of testosterone roiled in front of them. These young ladies were similarly decked out — highly adorned, some with huge bead collars layered above their bare breasts, which they tipped back and forth as they bobbed to the rhythm. Eventually these young ladies joined the group of young men, and they paraded back and forth along the dirt road, chanting all the while. The show seemed to go on forever, and the stamina of the young men exerting so much energy leaping into the thick air on a scorching afternoon was awe-inspiring for us looky-lous who were wilting in the heat.

As for the bride? Honestly, she did not look happy. When we presented the goat (which was loudly complaining about being held by its ear) to the bride and groom, just outside the circle of the low, rounded roof, stick huts that made up the village, it wasn’t hard to understand why. He was very much older and a bit worse for wear; she might have been his third of fourth wife? His choosing her, in essence buying her with a dowry of cows, goats, and/or camels, meant that she would leave her mother, her siblings, her friends, her village, and go to live with him somewhere possibly quite distant. She would have most probably not have met the groom until their wedding.

It is easy to look on all of this critically, but I feel it is important to be respectful of the traditional ways of the Samburu people. They certainly appear to have much pride in their own traditions, and the girls are brought up in this system, as were their mothers, and their grandmothers, for time immemorial. The burgeoning use of cell phones, that so easily offer a portal to the world beyond Nemunyak, will no doubt generate some significant changes within their close community. Slow change is already happening with the gentle empowerment of women through employment at the Sarara lodges and Reteti elephant sanctuary, and for the many women who are selling their goat’s milk to the sanctuary, and so for the first time, have their own income.

The Sarara Foundation also funds a mobile medical clinic that especially supports maternal and newborn health, and as well funds a mobile Montessori school. Being nomads spread out over a huge area, offering fixed clinics and schools for the Samburu would make them practically inaccessible for many.

Reteti Elephant Sanctuary

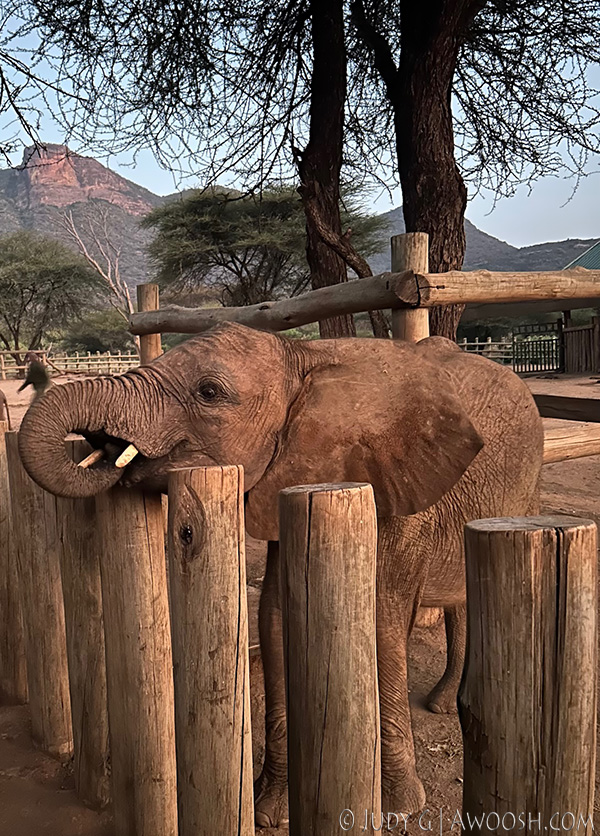

We were offered a morning excursion to visit the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary. This is another inspiring project, and was one of the highlights of our time at Sarara. The only completely community owned and staffed elephant sanctuary in Kenya, Reteti accepts lost or orphaned young animals from all over northern Kenya, and protects and nourishes them until they can be safely re-wilded. They have a great track record so far, and since opening in 2019, they have successfully released 23 elephants, 36 giraffes, 40+ Gerenuk and other African antelopes, and 6 Colobus monkeys and baboons.

Our guide, Naomi, a local Samburu (as are all of the employees) gave us the tour. After a very dark o’thirty start and a bumpy ride across the valley, we arrived at daybreak, just in time for the 6 am feeding. Numerous keepers appeared with big bottles of prepared goats milk, and then the young elephants moved in quickly to get their feed on. Like human babies, some of the little ones fed from a bottle held by the Samburu sanctuary staff. Others, a bit older, greedily grabbed the bottles out of their hands with their agile trunks and sucked them back with astonishing speed, tossing them in the dirt when they were done like a redneck’s just chugged beer can.

The elephants are fed every three hours, around the clock. It is an incredible commitment for the sanctuary to provide both the staff and the huge volume of goat’s milk to be able to do this, and it would not be possible without the Sarara Foundation, as well as much needed donations from individuals around the world. Please go to Reteti.org to learn more about the wonderful work that they are doing in Kenya, and how the sanctuary is benefitting not just the animals, but also the local Samburu community. You can help by making a donation, and you can even ‘adopt’ a baby elephant!

And it is not just elephants that are being saved at Reteti, there is also a population of young giraffes, some ostriches, some varieties of African antelopes, a few simians, and a tortoise or two. Our group were all given the chance to bottle feed a giraffe or an antelope while we were there.

As the animals mature, the keepers, with whom they clearly form attachments, accompany them out into the wild areas surrounding the sanctuary, and they help to teach them to browse, just as their mothers would have — which includes hand feeding them the plants that are safe and good for them to eat. When the elephants reach the age of 6-7, they are ready to be released back into the wild. The released animals are electronically tracked, and so that know that several of their elephants have managed to somehow reconnect with their matriarchal family groups — sometimes after traveling over huge distances. It is said that an elephant never forgets, and this for sure is a confirmation of that!

I already loved wild elephants before we visited the sanctuary, with their soulful eyes and comedic expressions, and their pure majesty as massive herbivores that gather in co-operative and protective communities. That adoration was forever cemented by being loved up by one of the young female elephants at the sanctuary — although we were asked not to touch the elephants, she definitely initiated gentle contact with quite a few of us. She laid her sinuous trunk like a blessing over my head and held me for a long time in a heartfelt elephant hug. Magical. We were asked not to share photos, as they don’t want people going there thinking that they are going to pet the elephants.

And then, just like that, Sarara was in the rearview mirror as we moved on to our last location, the Maasai Mara North Conservancy.

Click for Part 4 – Mara North Conservancy — Elewana’s Elephant Pepper Camp