This is going to be a very, er, explosive blog bit – because when I referenced “getting bombed in Bima”, I am not talking about inhaling too many Bintang beers ;^)

Our up close and personal bombing experience was provided courtesy of local Indonesian fisherman – likely residents of the large island of Sumbawa, which lies between the islands that comprise Komodo National Park (to the east) and Lombok (and then Bali), to the west. They were brazenly dropping their fish bombs in plain view of the live aboard we were diving from – the Komodo Dancer, and the blasting was occurring within Bima Bay – a large, populated inlet on Sumbawa Island. The culprit was not more than a half mile or so away.

Known as “dynamite fishing”, this practice is still pretty rampant in some of the poorer countries of the world, and apparently evolved out of fishermen figuring out how to use postwar munitions to catch lotsa fish.

Dynamite is a bit of a misnomer – there are apparently many different explosives used, including gasoline and fertilizer – all of them crude. It is a deplorable practice for several reasons – primarily due to the unconscionable devastating destruction of coral reef habitat (more on that later), and the significant by-kill (that is, creatures killed that are not the primary targets and are non-consummable). Blast fishing is also a very hazardous occupation for fishermen, which includes untrained guys on scuba bobbing up and down to collect the sunken kill and getting themselves seriously bent in the process. I am not aware of any recreational scuba divers that have been killed by blast fishing, but it is clearly a possibility. I know a few other divers who have shared harrowing stories of being too close for comfort while blast fishing occurred nearby. The closest I had been to this kind of activity was while diving at Richelieu Rock in Thailand. We heard loud booms while underwater there, and we were told that the bombing was happening in Myanmar (formerly Burma) – about 20 kilometres away. Even then it was unnerving.

Our morning started out pretty benignly. We had made the transit overnight from Sangeyang Island to Bima Harbour after the gnarly current night dive. We awoke to a calm bay and a pretty sunrise. After the “first breakfast” (self-serve coffee, juice, toast, fruit, pastries), we were briefed on the plan for the day – four muck dives in the harbour (including a night dive), on a site called “Fuzzy Bottom”. Michael gave us a good briefing with an idea of the weird and wonderful critters we could hope to see, and all of us macro loving photogs were pretty pumped at the prospect.

And it was a fuzzy bottom, comprised of deep silt and some detritus (although nothing in the order of the garbage strewn at some of the sites in Ambon Harbour – also home of some epic muck diving). So not a pretty site, but definitely some very cool denizens.

Our small group (thefishhead, pismodiver, Mr G and me) were the first to be dropped in, led by Michael. Right off the top Michael found a coolio yellow pipefish, so we all stopped to admire it and then lined up to take a couple of shots of it, as Michael finned on into the gloom looking for more cool stuff to show us.

BANG!!!!! I felt a large concussion in my chest. I wondered if someone’s first stage (the top part of a regulator, that attaches to the tank) had blown nearby, and looked around our group. Everyone’s equipment was fine, but we all had big eyes that clearly communicated WTF Was That? The visibility was maybe a murky twenty-five feet, so we couldn’t see the other groups of our buddies.

We all hung there for a couple of minutes to see if there would be a diver recall (when the boat needs people to surface immediately, there are signals they can give – most usually steady hammering of a metal tool on a metal ladder on the boat). Michael had already disappeared into the gloom, so there was no way to ask him (using underwater sign language) what was up with the big bang. After a couple of minutes, with no further excitement and no recall, we all shrugged it off and carried on.

In the poor visibility I became disconnected from Dave and the girls fairly quickly; I was not worried about it – there was no current, we were quite shallow (about 30 feet), the site area was not huge, and we were all headed in the same direction. I figured we’d all run in to each other again sometime during the dive (which we eventually did). So I was alone when the next couple of explosions occurred, a few minutes apart, and let me tell you it was pretty damn freaky. After the second one, I knew this had to be blast fishing, and it felt very near by. The explosions had shock waves that I felt strongly to my core and caused my heart to race. I could hear an engine running above, and I started to cook up the paranoid possibility that we were actually being targeted. Were these arseholes looking for white western tourist bubbles and dropping their malatov cocktails deliberately on us – could it be a message in a bottle from Indonesians who didn’t want us in their area?

I had a light foundation for my fear – we had transited through Sumbawa Island a few years previously on a family trip to Komodo. There was a definite feeling of non-welcome to Westerners on the island then. I wrote about that here – you’ll have to scroll waaaay down to get the part about Komodo and our hair-raising experience on Sumbawa.

But this was not the case – as I mentioned earlier, the culprit fishing boat was at least a half mile away, but sound and shock waves are readily transmitted underwater, and we were all feeling them, bigtime. It is possible that the fishermen have no idea how loud, and how destructive these blasts are, under the surface.

I shakily carried on, running in to Michael a while later. Employing charades-like gestures, I asked him Wassup with the booms? Using charades-like gestures, he responded F*cking Fishermen. And: Don’t worry, it’s okay…

Soon after, the bombing stopped. I finally started to take some deep breaths and relax into the dive. I am not sure what it says about my level of commitment (or sanity) that I stayed in the water after such unsettling happenings ;^)

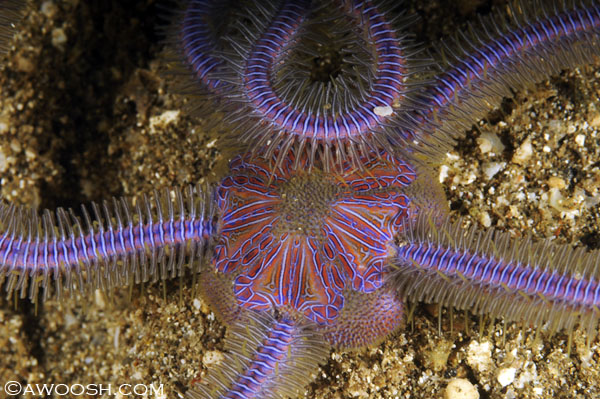

(Edited) Purple-banded Brittle Star – Ophiothrix nereidina

Many thanks to Doc V for for the positive identification.

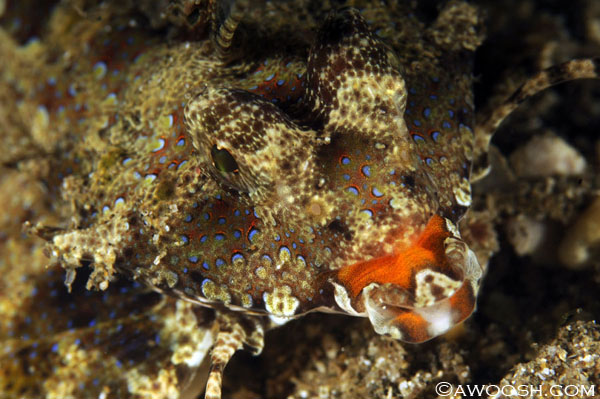

Orange & Black Dragonet – Dactylopus kuiteri

This is a very strange bottom dwelling fish that typically creeps along, although it can swim.

Ready for its close up. These animals are fascinating in that they can change colours and shapes to mimic other reef critters. I have seen this kind of octopus flatten itself out to the sand, and try to pass for a sole.

When we got back on the boat, we were all abuzz with nervous chatter about the bombing incident(s). One of our group, a very experienced diver but new to Asia diving, admitted she freaked out and bailed on the dive. Everyone else stuck it out, but the inimitable Miss Gills told us the story of how, after the second blast, she had swum up to her group’s guide, and using similar sign language that I referenced above, told him to get his arse to the surface and find out what the heck was going on. He was picked up and taken back to the main boat by the panga (so probably the engine overhead that I heard), where he told the Captain about the situation. The bombing would not have been nearly as noticeable from the surface – most of the energy of this kind of blast stays underwater. Some sort of communication ensued; the bombing stopped.

So I guess I could try to shrug this all off and say it is a cultural practice and as affluent Westerners who are not facing the harsh realities of living hand to mouth, we do not have the right to share an opinion about such things. Or I could stay quiet (as some of our group thought we should) for fear that reporting this incident would deter people from going to Komodo (and even Indonesia) and in doing so, harm the dive businesses there.

Michael Ishak, himself Indonesian, who was the boat’s Cruise Director for this trip, urged me to do otherwise. He wants the world to know, and for pressure to be put on the Indonesian government to outlaw this practice – and to enforce those laws. He has a front row seat to the complex and corrupt issues around blast fishing in Indonesia, and specifically within Komodo National Park. In fact, earlier in the year he documented (photographically) some areas of recent reef destruction, within the park – where no fishing is supposed to occur, and went public with it. His images and commentary were picked up by the international news media, and as a result, Michael himself became the recipient of some death threats by area fisherman. Geez, if I had known that before the Bima dives, I would’ve asked to be in someone else’s group ;^)

Seriously though, the situation should be of great concern to us all. Komodo is a phenomenal ecosystem and a nursery for many, many varieties of fish. The destruction of huge swathes of healthy coral reef for the catch of the day is both short-sighted and non-sustainable. Many corals take hundreds of years to grow – these reefs won’t be coming back to life for generations to come. If you destroy the reef, you kill the habitat. If you kill the habitat, there will be no more residents. The ocean is a veritable chain of life, and coral reefs are a critical link in it. If food protein supply for folks is the primary issue, why not promote and support raising game on the lush and beautiful islands in the area? Chickens, ducks, farm mammals – they would all prosper on this fertile land, and could be sustainably farmed.

The politics and the protection of Komodo National Park are complex, and I highly recommend that you follow this link to read an informative article written by Douglas Siefert, which explains the history and the challenge of conservation of KNP far better than I could.

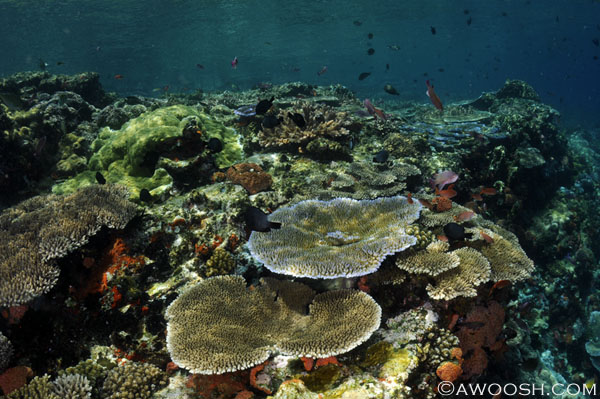

As it ends up, on our last day of this glorious, highlight-filled trip, we dove an area within the park that had recent evidence of blast fishing – not very far from the port of Labuan Bajo. As Michael described it, it was a signature Komodo dive site – fishy, with abundant and varied coral gardens – right up in to 10 foot shallows. I can only imagine his shock and horror when he dropped in for the first time of the season (well before our trip) and found huge swaths of destruction – flattened corals, sea fans uprooted and tipped on their sides, boulders relocated, nary a fish in sight. This area had been blatantly bombed, in the dive off-season, and the perpetrators got away with it. Although I usually prefer to try to find beauty in the things I photograph, I too felt the need to document the sickening devastation, and I knew I had to share it.

Michael says, even in the Komodo high season, there is currently little to no patrolling happening. The fishery enforcement boats, bought with fees collected from tourists visiting Komodo National Park, now sit rotting in Labuan Bajo harbour. The only patrol boats out in the expansive park seem solely intent on making sure visitors have paid their park entry fees. The fishing appears to continue unchecked.

There will be a second installment of Bima muck images in the next post, as there are a lot more of them I would like to share. But today, as a footnote to a sad saga about reef destruction, I leave you with this contrast:

Chapters of the Komodo Chronicles:

Chapter 1 – Here We Be

Chapter 2 – Time to Rock and Roll

Chapter 3 – Champagne Diving and Nudibranch Dreams

Chapter 4 – Things That Go Bump in the Night

Chapter 5 – Getting Bombed in Bima

Chapter 6 – The Muck, And Nothing But The Muck

Chapter 7 – Rinse & Repeat

Chapter 8 – Back In The Blue