The iconic Reichstag. Probably the most recognizeable of all buildings in Berlin, thanks to film archives of Hitler’s rants, er, rallies on the steps. And this picture doesn’t really do it justice – it is H.U.G.E.

So here I am, once again leaving Berlin, after Mr G conducts some business here. I have been fortunate to be able to visit this beautiful city, albeit with a very dark history, several times over the past eight years or so. I always intend to blog when I am here, but somehow in the fugue of jet lag and late nights out drinking Pils (good German beer) in one of the many bars, I never quite get around to it. So let this be the beginning of a series of bits I will write over the next while about Berlin, and other travels in Germany.

Germans are funny people – literally – they have a keen, although at times, peculiar (at least to this Canadian) sense of humour. Ultimately, all kidding aside, they are a very orderly society (except when factions break out in riots on May Day every year – more on that in a future post). This orderliness is symbolically reflected through the architecture of Berlin – imposing if not overly beautiful buildings (with a few exceptions), straight streets, grand boulevards, stately statuary and linear parks.

Berlin is a visitor’s city – rich with history, both ancient and modern – and equipped with ample tourist infrastructure. Grand theatres, cathedrals, museums and galleries abound. There are river cruises on the Spree, Hop On Hop Off bus tours, bicycle tours, Trebant (the strange little cars of the DDR) tours, multi-passenger spinning and beer swilling tours on some very strange contraptions, and even Segway tours. There is also a huge choice of restaurants, bars and nightclubs.

Almost all the historical buildings of Berlin were heavily damaged or flattened during the Allied forces bombings late in World War II, and much of that destruction was left in ruins during the post War era of the DDR. Most of Berlin’s historical cultural center ended up behind the Berlin Wall, and so in Communist control. Instead of rebuilding these artistic and religious monuments, they built huge, monolithic, ugly, minimalist buildings around or over the ruins. Since the fall of the wall in 1989/1990, a lot of those Soviet/DDR structures have been torn down – but the surreal Fernsehturm (television tower) continues to dominate the sky scape in East Berlin. Most of the historical buildings have been reconstructed in an apparently incessant and expensive process to bring Berlin back to its former glory.

On my first visit to Berlin, I arrived with an enquiring mind – specifically, how do modern day Germans deal with their tragic history – a history that is not so ancient? It is not a question of blame or guilt – after all, the perpetrators of the horrendous Holocaust before and during World War II are not these modern day people strolling the boulevards and sipping beer in sidewalk cafes – they are only (possibly) the descendants of those who either perpetrated the crimes, profited from them, or turned a blind eye to them. Just as I do not choose to feel guilt for my own family’s dark chapter in history (which I only learned of a few years ago, when my father was researching his family tree and discovered a rotten root) of slave transport from Africa and trading in the Caribbean in the 1800’s, these modern day Germans should not be expected to shoulder any sort of collective guilt for the crimes of their forefathers. But yet, I sense, at least some do. And if not guilt, maybe at least a sense of shame. Others, I believe, choose to blame the Treaty of Versailles that created huge hardship for Germans post World War 1, and “the mad little Austrian”, for all the insanity that befell Germany during the time of Nazism.

What I was really interested in was this: how is this history physically and/or symbolically represented within Germany, and how deep do you have to dig to find it? Is it available, as an example, to high schoolers on field trips? Is it even taught in schools?

It has taken me a few years to really get any kind of answers to these questions. The short deal is this: that as long as you are willing to dig a bit for it, you can find the telling of this history in Berlin. It certainly is not loudly trumpeted on every street corner, but it is there for those who feel the need to enquire.

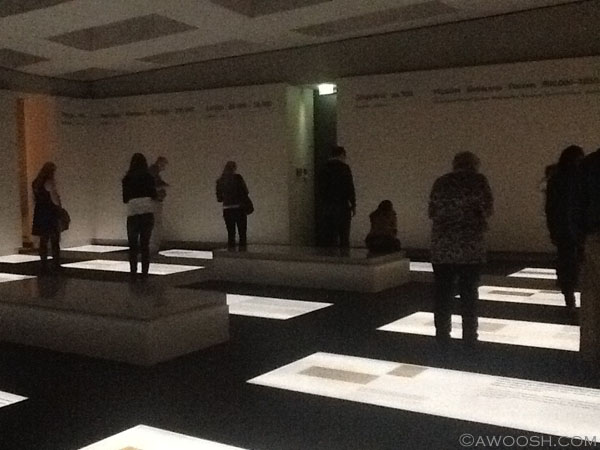

The most accessible and gripping of all the representations and explanations of the Holocaust that I have seen in Berlin is in an underground Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe museum (not unlike a modern bunker) – located beneath a “Field of Stelae” (which look uncannily like anonymous above ground tombs or sarcophaguses). This memorial is located in a very central area of Berlin (right across the road from the American Embassy). It is my understanding that the architects (Eisenman & Happold) of this huge city block of 2711 concrete slabs were not attempting to be quite that literal – it is explained that the intention is “the stelae are designed to produce an uneasy, confusing atmosphere, and the whole sculpture aims to represent a supposedly ordered system that has lost touch with human reason.” No matter which way you look at it, it is stark and somehow very unsettling.

So this, and the remainder of the pictures shared in this post were shot with my iPad. Actually, not a bad camera, considering it is part of a tablet computer. Just strange for me to let the camera make all the decisions about ISO, aperture, shutter speed etc.

These are just an iPad lens full of the couple of thousand of the “stelae” that make up this stark, yet moving sculpture. You can just make out the US flag on the building behind it – this is the US Embassy in Berlin.

In fact, I visited this museum on this trip, and was profoundly affected by the somewhat minimalist but very logical representation of the linear events that lead to the ultimate execution of what is estimated to be between 5.5 and 6 million Jews, homosexuals, disabled people, gypsies, Russian prisoners of war and enemies of the National Socialist Party (aka the Nazis), from 1938 to 1945.

Visitors literally walk down the timeline – from the beginnings of Nazi persecution of the Jews in Germany, to the widespread genocide that occurred in numerous countries in Europe as Hitler and his henchman sought to kill every Jew in existence as far as they could reach.

I have to add that for me, the most educational and impact filled experience of a Holocaust Memorial has been in London – at the Imperial War Museum. There, the viewer walks through an entire floor devoted to explaining and viscerally sharing the experience. The voices of survivors describing their descent into hell are unforgettable, as is the large scale model of a concentration camp, and the personal belongings of just a few of the millions murdered. This all adds up to a more human element that I found a bit lacking in the Berlin memorial.

Still, the portraits, the chosen stories of Jewish families from around Europe and what happened to members of them, and for me, most poignantly, the remnants of postcards and letters written by people on the way to their uncertain and terrifying futures packed into cattle cars on trains, all combine to make a visit to this memorial museum both an educational and emotional experience.

Visitors to the memorial read poignant fragments of last correspondences of people, who were on their way to certain death.

In future posts, I’ll visit other notable (and maybe less controversial) attractions, in Berlin, as well as share some stories and images from Potsdam and Dresden. Oh, and I’ll take you on a photo tour of Sachsenhausen – the “prototype” concentration camp, which is located very near to Berlin.

Until then, gute nacht, lieber leser.

PS – the title of this post is a reference to the fantastic book about World War II, including the Holocaust, by Herman Wouk. It’s actually two books – Winds of War (which I am currently reading), and then the follow up – War & Remembrance. I first read these wonderful novels in the late 70’s, and liked them very much. I recently waded through, er, finished Ken Follett’s Pillars of the Earth (about World War I) and I will admit that I didn’t love it. I thought some of the writing was pretty lazy, and the characters too simply drawn. I recalled really enjoying reading Wouk, so I downloaded Winds of War, and War & Remembrance, to my iPad, and the rest, as they say, is history. I really can’t recommend them enough – fantastic stories with rich characters, written over factual history. To be reading Winds of War while in Berlin has been slightly surreal, but very rewarding.