Indonesia Immersion

Text by Michael Southard

Question: Answer: So fifteen old friends and new acquaintances decided to meet on geographically obscure Ambon Island to spend ten days diving the rich and often pristine local waters, as well as to sail to and dive the even more obscure Banda Sea region. After arduous journeys from diverse starting points all over North America, and against strong odds, the lucky group managed to safely reach Ambon City where our home for the next 10 days, the Archipelago Adventurer II, was moored in the harbor. We were met at the Ambon airport by the boat’s Cruise Director, Simon Buxton, who escorted us to a dock. From there, some of the AAII crew transported us to the ship via rugged, unsinkable aluminum skiffs – the same small boats that would shuttle us from the mother ship to the dive sites throughout our journey. Even as we went through the routine of gathering all our tons of gear and getting it safely on board the skiffs, the quality, and for that matter, the quantity of the AAII crew was becoming apparent. Smiling faces and pleasant, helpful attitudes greeted us from the start. And these were not affectations – our crew was genuinely a happy lot, and the service from top to bottom was nothing short of splendid.

The AAII is a decidedly handsome vessel, a wooden motor-sailor purpose built as a dive platform. While under full sail she is reminiscent of elegant 19th century schooners, but in truth the sails are strictly for show and were only raised one time during our trip. For the rest of our journey, the single screw diesel engine pushed us steadily, albeit slowly, through the calm Banda seas. The wide beam and shallow keel made for a stable platform when moored, but at sea she tended to gently wallow along like a corpulent hippo fording a stream. The water-level gangplank/stairs led up to one of the two gearing-up stations located on either side of the ship, and from there we entered the ship’s roomy and comfortable salon to begin orientation, room assignments, and briefings. The salon is the heart of the AA – a gathering place, camera room, massage parlor, battery charging station, nap cubby, snack distribution center, and entertainment hub. The first order of business was getting settled into our rooms. There were many, many pleasant surprises on this adventure, but few any more pleasing than the first peek into the AA’s guest quarters. My “Wow” echoed three times in the commodious space! Well, not really. But if you have a few live-aboard experiences under your belt, bunking in claustrophobic, coffin-sized cabins, you know exactly what a thrill it was to see these lovely, spacious rooms. Lots of light, lots of storage space, generous en-suite facilities, even a well-lit desk on which one could jot down notes for a future trip report. But there was little time to relish our palatial quarters; there was work to do. These waters needed diving, and we were just the folks to do it. But first, we were formally introduced to the crew and learned about the procedures of the boat. Our group was first divided into three dive teams. We went with a light load of fourteen divers, but the boat can handle eighteen divers comfortably. Each day, the teams would dive a staggered schedule, which allowed the three teams to work around the fact that the AAII only had two dive tenders and, inconveniently, only two sides. For the first dive of the trip, we assembled our kits on tanks in racks at our station on our assigned side of the ship, tested Nitrox, checked fills, and put ID marks on our stuff. The crew then loaded our rigs onto the skiffs while we suited up. For the rest of the trip, the crew handled all the gear for us except suits, masks, and cameras. The briefing for each dive was held on the open deck at the bow of the ship. The briefings were often as entertaining as they were informative, and nearly every briefing was punctuated by Richard (aka Sapien), the lively lynchpin and tireless organizer of this trip, pantomiming the elusive pom-pom crab he so dearly wanted to see. Upon completion of the briefing, the first two teams would depart for the dive site to stir up the silt and scatter the critters for the third team. The traditional checkout dive was to be right there in Ambon Harbor, and for many of us this would be our introduction to the fine art of “Muck Diving”. Many divers have heard of but have not experienced this unique dive experience, and perhaps many more would try it if the name didn’t sound so unappetizing. Each of our group, however, had scoured the internet in the long months before the trip began, and though specific information on Ambon was a bit hard to find, what there was of it extolled the superb muck environment to be found here. So we were ready to be wowed, and folks, we were not disappointed. Muck diving, in short, is diving in areas of rich and abundant marine life where there is a soft, sandy, and mostly featureless bottom, rather than coral or other mineral structure. At first glance, these areas are dull and lifeless, but that is only because the creatures who have adapted to this habitat have had to evolve the most clever, creative, and quite often bizarre features and behaviors to survive where there is little or no cover. Muck diving does require that you sharpen your eye, avoid stirring up the silty bottom, and carry a stick. Not just any stick – a Muck Stick. A Muck Stick is a 15-or-so inch aluminum or fiberglass rod with a wrist strap attached. It is used variously for pointing at creatures, as a monopod for the camera jockeys, and most importantly, as a personal mooring in the sand when the sometimes fickle Indonesian currents began to blow. They are also handy back scratchers. The weather was clear and the skies were sunny as our group boarded the tender, and while our guide helped us get sorted and rigged for the dive, our driver pulled to life one, then the other outboard engine, and we made the short trip to the selected spot for our first dive - Laha. All divers entered the water together by back roll, and we found ourselves in delightfully warm, if slightly funky, 84°F water and working our way down to the dark, featureless bottom. We barely had a moment to acclimate to this strange setting when our guide started waving divers over to view some odd creature or another. For the many photographers on the trip, it was a sensory overload of the most delicious sort. There simply wasn’t enough time to allot to each extraordinary new subject before you would glance up to see our eagle-eyed guides had found something else. It was nearly overwhelming. It was wonderful! In notes thoughtfully provided to us at the end of the trip by Simon, recalling details of each dive, this single dive yielded: two sea horses, three Pegasus Sea Moths, many crinoid cuttlefish, two Leaf Scorpionfish, two ribbon eels, T-Bar nudibranchs, Coleman Shrimp, and zebra crabs riding on the backs of fire urchins. And that is just what Simon saw; there were seventeen divers in the water.

With smiles on our faces and hundreds of images on our various memory cards, it became time to begin wrapping up the dive. To the credit of the crew, and indicative of protocol for the rest of the trip, solely the air remaining in our tanks determined that time. Dive times throughout the trip averaged an hour, and ranged up to 90 minutes on the shallower dives on AL 80’s. One by one the divers surfaced, to be immediately picked up by the tender, offered chilled bottled water to drink while waiting for other divers to finish, or quickly shuttled back to the AAII if it seemed there might be a long wait. After the dive, you simply left your kit on the tender and climbed back up to the deck where you would find a freshly laundered towel in your spot, and a hot shower on the dive deck to rinse off the salt. One of the crew would take your wetsuit for you, rinse it, hang it to dry at the bow, and it would appear before the next dive neatly folded at your station. There was a large camera rinse tank and large, outdoor, covered camera tables on each side of the boat, as well as lots of table space and a charging station in the main salon. The rinse tank water was changed regularly. Once back on board from this stellar first dive, there was a little time to wander the boat and get our bearings. I was having my usual difficult time getting names and faces of the crew committed to memory, but this time with good reason: the crew of sixteen outnumbered the guests. Fifteen were Indonesian locals, plus our British expat cruise director, Simon. I believe I can speak for our entire group when I say that we simply could not have had a better crew for this trip. And I also believe that there would be no argument that Simon deserves a bit of special recognition. Simon wore many hats on our trip, for not only did he act as Cruise Director and Purser, he held most of the dive briefings, and joined us on almost every dive as an enthusiastic guide. And, to the great good fortune of the photographers on board, Simon is an accomplished and well-published professional underwater photographer, and he was very generous with his advice and council on the subject. From technical hints, to helping solve camera problems, to guiding us to great photo set-ups, he was a greatly appreciated bonus for the photogs aboard. The two local Indonesian Dive Guides, Ali and Made, are also worthy of kudos. From Ali's infectious giggle to Made's determination to make sure everyone saw something special he had spotted, these guys went above and beyond on every dive. We were all looking forward to our first meal on board, as the AAII literature extols its exceptional cuisine, and dinnertime arrived soon after our dive. Whenever possible, dinner was served al fresco on the top stern deck, which was partially covered and offered beautiful sea views while we dined. On the occasions when the weather was either too rainy or too hot, there was also an indoor dining room with comfortable AC. Except for breakfast, most meals were casual buffet style, and the offerings ranged from local Indonesian satays, noodles, rice dishes, and curries, to fresh fish, steaks, and potatoes, along with fresh salads, breads, and simple-but-tasty desserts. Breakfast orders were taken before the first dive from a limited and unchanging menu, and were served a la carte. Light Continental Breakfast fixings (coffee, juice, toast, pastries) were available before the first dive. Between the puffing about the food on AAII’s website and my deep love of food from this region, I’m afraid I set my expectations a bit high, and while there were some standouts and exceptional meals along the way, overall I would have to give the food a strong “B”. Occasionally, the portion sizes for plated dinners were not quite up to American Diver appetites, and seconds were not available. I personally was hoping for more adventurous offerings featuring the big flavors of the region, but instead I found myself adding pepper and hot sauce to dishes likely intended to not offend a bland tourist palate. To be fair, some of us found the food excellent (the vegetarians in the group were particularly very pleased with the offerings), and we all were bowled over by the skill and attentiveness of the food staff and the beautiful presentation. Service was impeccable. The only other minor quibble about the food and beverage service were the rather usurious prices charged for beer and wines on board – $7 a glass and $35 a bottle for very average and inexpensive Australian pours, and $4 for local brews that retail for about 40 cents ashore. Soon enough, it was time for our first night dive, which usually began at dusk and lasted solidly into the darkest night. The first teams suited up and boarded the tenders, and found our rigs perfectly set up (even my wonky back-mounted pony tank was set up correctly) and our fins placed neatly at our feet. We felt spoiled. It was great. Night dives in Indonesia are special. I enjoy night dives under any circumstances, but the array of critters that come to the party after dark in this part of the world made them even more extraordinary. Because of crossings and land tours we only got in six night dives on this trip of nine diving days. Of the six dives, five were muck dives in various protected harbors and bays. As you might imagine, the inherent strangeness of muck diving is amplified by removing light. The visibility on muck sites tends to be less than reef dives to begin with, and even the most careful divers will inadvertently stir up some bottom silt while pausing to observe a creature. Dive lights dulled and diffused by the suspended particulate add to the surreal nature of these dives. Divers moving only 30 or 40 feet away appear as a spooky glow. Some of our dives took place near rickety wooden docks or beneath moored vessels that created eerie silhouettes, and invariably we would come across numerous articles of human debris ranging from clothing to appliances. And if all that wasn’t quite enough to make for unique (not to mention occasional yucky) muck diving, add in a stiff tidal current that varied from a tiny trickle to gale force, sometimes enough to require burying your muck stick for an anchor or holding on to whatever meager outcropping that might be handy to avoid being swept away.

To all this, add the most wonderful displays of creatures and behaviors I have ever seen. From football-sized Black Painted Frogfish waddling along the bottom, to octopi engaged in cannibalism, to crustaceans and nudibranchs and scorpionfish in astounding numbers and variety. There were juvenile batfish, mandarinfish, snake eels, and so many sea horses that they almost became ordinary. But there was a handful of very special creatures that inhabit these waters that we all were hoping to see, and as you will read throughout this report, luck was with us. In Hila Bay, North Ambon, I was concentrating on a shot when I noticed a light beam flashing in front of me, a signal from another diver that there was something worth a bit of swimming to see. I finned over to the source of the light and Jamie (aka Peaches), from our group, pointed excitedly to a small piece of coral. For the life of me I could not detect anything unusual. Finally, frustrated, she moved her gloved hand even closer and a tiny octopus moved, and immediately I recognized the unmistakable markings of the mortally dangerous Blue Ring Octopus. It swam from the reef in open water for a few moments, then settled on another outcropping, spread to its most menacing half-dollar size for a moment, and then retreated into a crevice. It was a remarkable find, and before long there were more divers following it around and snapping photos, ignoring the fact that one bite from this creature would be absolutely fatal. A bit of comic relief took place when Simon lost the little devil in mid-water from the viewfinder of his camera, wisely dropped his precious rig to the bottom, and then examined it very warily until the exact location of the octopus was re-established.

I’ve jumped ahead a bit – where were we? Oh yes, finishing up our first day of diving in Ambon Harbor. While the general itinerary was planned out, there was flexibility in the schedule to accommodate requests by the passengers, so we wasted no time making one: Would it be too much trouble to spend another day right here in Amazing Ambon? No, it wouldn’t, so with the agreement of everyone concerned we spent another full day happily mucking about in the harbor. A second night dive was also offered by Simon this first evening on the boat – which was only taken up by one of our group (Judy G). How many boats have you been on where three dives are offered on arrival day? I’d wager not many. On day three, we finally weighed anchor and headed westerly out of the harbor, to begin a slow clockwise circumnavigation of Ambon Island, stopping and diving the clear waters and pristine reefs along the way. Yes, there is more to Indonesia diving than muck, although I must admit I was enjoying the muck diving so much I could have happily made a whole trip of it. That would have been an unfortunate choice, because once we dropped in on the healthy and varied reefs we all realized what great diving we might have missed. The first reef dive of the trip proved to be just as exciting and wonderful as the muck diving had been, and produced schools of giant snappers, a school of reclusive Bumphead Parrotfish, and a vast, seemingly unending parade of Red Tooth Triggerfish. The visibility was near 100 feet, and the health of the surrounding reefs rivaled or exceeded that of any dive location I have yet visited. We also got another taste of the healthy currents common to this area, and those not accustomed to dealing with them got tuned up quickly. With current this strong, and in such remote locations, one must be mindful of the location of the group and keep it a little closer than usual, and keep a watchful eye on air consumption as there is a lot more “uphill” swimming involved.

On our second dive of the day, we really got a taste of serious current. From the moment we descended, we were sweeping along and my buddy for the dive, Cindy (aka Gunard) and I dropped in behind a coral outcropping and held on to some dead coral while wordlessly formulating a game plan. I had never experienced such current, so I suggested we abort, but Cindy indicated we should wait a bit and see what the group did. The group was spread across the bottom, all holding on to something or swimming at full speed just to stay stationary. After a few minutes, a couple of divers let go and began to ride the current, and soon we all joined the migration. Minutes later, we noticed a long, sturdy rope strung as far as the eye could see from left to right, and the first of our group grabbed the rope and held, and before long all of us were hanging from this rope in a line like laundry in a stiff wind, all of us motionless and yet horizontal in the relentless current. I attempted to take a picture of this now humorous predicament, but the current was too strong to allow me to operate my rig with one hand. Luckily, Bill M had his small point-and-shoot camera and was able to memorialize the moment. Another few moments of indecision passed, when suddenly the rope gave way, slackened a few feet, then caught again. That startled us into action, and we all released and took the ride of our lives along the reef, probably for a mile or more, until the current slowly began to abate and then lessened to a manageable trickle for the remainder of the dive. It was an exhilarating dive, and truthfully, it was a barrel of fun. But it made us wary, and later in the trip the current had other surprises in store for us.

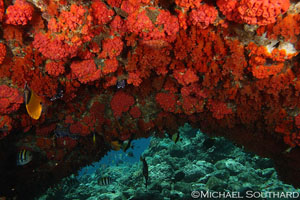

Moving east on the fourth morning we passed the along the northerly coast of Ambon Island, then spent much of the morning navigating southward through narrow straights between Ambon and the Uliasers, arriving in time for a pre and post-lunch pair of dives off Mamala Island, where a lucky few had sightings of black-tipped sharks and dog toothed tuna, rare sights now due to intense fishing pressure in the region. For the late afternoon dive we motored over to nearby Nusa Laut. The dive began by passing through a beautiful swim thru en route to an area with sea fans known to be the home to another very special creature, the Pygmy Sea Horse, but none were to be found. At least not yet.

That evening the night dive had to be forgone to allow time for our longest open sea crossing, a straight shot from Nusa Laut to the historic Banda islands. We slept soundly during the smooth and uneventful crossing, and we awoke anchored safely at our destination. Morning dives were skipped to accommodate a shore excursion to the main island of Banda Basar. Before our journey Richard (aka Sapien) had very kindly sent each passenger a book on the rich and varied history of Banda, which was a major player from 15th through 18th century politics and commerce due to the rare and valuable spices available only in this region, and the book added immensely to our enjoyment of the tour. Our Bandanese guide first walked us through the well-maintained museum where numerous artifacts are displayed, reflecting the (often grim) history of these islands. The Dutch had a very strong presence in Indonesia in the 17th and 18th centuries, dominating the local Indonesian spice islands so as to keep a secure hold on the international spice trade, which was extremely lucrative. The Dutch went as far as to import Japanese Samurai henchmen, who publicly beheaded all of the chiefs of neighboring islands in one horrific session. Our soft-spoken Banda guide told us "we forgive, but we never forget". The local school children were delighted to greet us, and happily accepted small gifts from Cindy as she strolled through the town. Despite the apparent poverty of this island, the children were all well-turned out in their colorful school uniforms, kept under the watchful eyes of their traditionally-dressed Muslim teachers. The high points of our tour were a visit to a working spice plantation, where we sampled spice teas and cakes and strolled through the dense and humid groves, and a guided tour of the 17th century Dutch fort located at a high vantage point. It was here we got a preview of a treat awaiting us back at the harbor. During our shore trip the AAII crew had unfurled and hoisted all of the sails, and our perch up on the steep fort walls afforded us a grand but distant view of our fine ship in her full glory. The shuttle back to the ship after our land excursion provided wonderful close up views of the decked-out vessel and plentiful photo opportunities.

We remained in the Banda islands for the remainder of that day and all of the following, logging six fine dives on the outlying reefs and inland muck sites of the harbor. On the afternoon dive we enjoyed a lovely swim through at 8o feet and observed flybys from Hawksbill Turtles and Napoleon Wrasse, and later that night we motored to nearby Banda Niera Island for a dusk dive at Nailaha dock to observe mating mandarinfish. While we were skunked on actual mating behavior, we did get to observe a few of the outrageously colored fish hiding in crevices among the stonework of the dock. Once the light was too dim for mandarin sightings, we moved off into the sandy bottom where we discovered the first 12-legged octopus in history, which later proved to be one octopus in the middle of dining on another. A snake eel three feet in length, reef cuttlefish on the hunt, and a long spine waspfish kept our interest until we emptied our tanks.

The next morning we did two dives on the three underwater pinnacles of Batu Kapal (Mushroom Island) where we marveled at some of the largest intact sea fans any of our group had ever seen. A school of Bumpheads buzzed us mid-dive, and two Banded Sea Snakes undulated through the jagged coral, leading photographers on a merry chase to catch an image of these highly venomous but docile air-breathing swimmers.

These dives were trip favorites for many of us, due to the wonderful variety of underwater structure and sea life. There were supremely healthy and pristine reefs and bommies, and great visibility, which made for a feast for both the wide angle photographers and the macro critter hunters. Near the perimeters of the site were extended areas of open sand containing nests of foul-tempered and toothy Titan Triggerfish, who aggressively defended their invisible boundaries against all comers. I myself had my fin latched onto and vigorously shaken by one of these fearless fathers, and I got off lucky, as another diver received a nasty looking bite on the thigh. No blood, but the point was made. Altogether, four of us were attacked, but Dave was the only casualty. Our group gave these over-protective parents a wide berth thereafter. We did one final day dive, a repeat back at Banda Basar, then hoisted anchor and set out on a short hop to outlying Suanggi Island, which was en-route back to Ambon. We anchored for a relaxing, current-free night dive and found 4 beautiful Saron Shrimp and an Ornate Lobster. After the dive, we motored overnight back to Nusa Laut where we revisited an area we enjoyed earlier in the trip and settled in for three successive dives on different parts of the same site. For the creature lovers, the site produced sightings of both Hairy and Elegant Squat Lobsters, leaf fish, crinoid shrimp, and large schools of jacks and giant snappers. Nusa Laut also had a nice distribution of brightly colored soft coral, reminiscent of some lesser sites in Fiji. And if the flora and fauna were not enough excitement, the third dive at this site gave us another serving of Indo currents which kept us all on our toes, requiring us to plan transiting swims carefully to avoid areas unprotected by reef structure, where the strongest currents were found. As if for punctuation, the second dive team was promptly swept off the site, collected by the tenders, and re-deposited up current for a do-over.

Before dinner that evening, we moved to anchor off Nalhaha Dock and dined while watching local fishermen in small outriggers working their gear and occasionally pulling in a fish or two, and later observed a particularly gorgeous sunset. Nalhaha was another muck site, and while we had hoped our night dive would provide a respite from the current we had battled all day, that was not to be the case. Managing brisk current, we found yet another trove of new (to us) creatures, including a Crocodile Snake Eel, Whip Coral Shrimp, petite and beautifully colored Bobtailed Squid, and nudibranchs by the score. I do not believe there was not a single night dive on the trip that did not reveal at least one, and often several species of nudibranchs, flatworms, or crustaceans new to our eyes.

The days flew by on board the AAII, and our morning sail on Day Eight to South Ambon signaled that our delightful circuitous voyage was soon to come to and end, and we were not ready for that despite the fact that our log books were brimming with copious notes from this trip already. It is worth mentioning that even though the AAII had four dives a day scheduled, compared to the five or even six available on other live-aboards, the most hard-core among us were feeling completely satisfied with both the quality and quantity of bottom time we were logging. Our dives were averaging well over an hour each, but even so our crew offered fifth dives on several occasions, which was accepted one evening and then declined after that. Four dives seemed just perfect. South Ambon held for us the promise of another chance to view, and hopefully photograph, Pygmy Sea Horses. These miniscule and fatally cute little fish were only discovered recently in this region, by a marine biologist studying the sea fans they inhabit. Full grown, these experts in camouflage can reach ½ inch in length, and many are closer to the size of grains of rice. They live out their lives on single growths of sea fans, which made it possible for our guides to locate them from dive to dive. On the first dive we waited while our guides meticulously searched for these prized creatures, and once one was found he motioned us down and we lined up for our chance to have a look. For eyes untrained in seeing Pygmys, it takes some concentration to separate their outline from that of the almost identical sea fan branches they have attached themselves to with their prehensile tails. Even with the tip of our guides’ muck stick only an inch away, I was unable to lock onto it with my eyes until, thankfully, it released and swam a couple inches to another branch. Keeping the little guys framed in my camera viewfinder was even a bigger challenge, especially since they shied from our focusing lights and immediately turned away once they were spied and framed. But our patience paid off and we ended up with some photos that made great memories of that dive. In all, six Pygmies were found on the two dives we made here, quantities that allowed each and every diver an opportunity to observe them.

On the second dive at South Ambon, we enjoyed exploring a swim through and several small caves, and during the course of the dive we came across three very interesting photo subjects. First, a couple of insect-looking Xeno Crabs living their days out on wire coral, and while waiting for a turn to view the Xenos I noticed one of the photographers taking shots of little ole’ me. Wondering why I was suddenly a photo subject, I shrugged to the cameraman who pointed to my left, where I found floating motionless a two foot long Cuttlefish only two feet from me. He evidently had been floating there unnoticed for several minutes, no doubt amused by all the hubbub and bubbles, and he seemed fearless and unperturbed while he himself became the object of attention of the group. He suffered our strobes patiently, then slowly moved on to other cuttlefish business further down the reef. Toward the end of the dive, one of our group discovered an enormous, bright yellow frogfish posing in a sponge, an ideal and easy photo subject were it not for the current which allowed each photographer one or two quick snaps as we were swept by, only to swim briskly up-current for another pass until we got a shot we were happy with.

The afternoon dive on Pintu Kota turned out to give a couple of our group a bit more than they bargained for. The current was ripping as our group descended down a line to the top of a beautiful coral encrusted archway, where most of us hovered close by enjoying sights such as a three foot long Map Pufferfish and mating nudibranchs. More stunningly healthy and huge sea fans were doing their best imitation of real fans, moving to and fro in the stiff flow. At the end of the dive, the safety stop became a fustercluck of the highest order as divers used a mooring rope attached to the reef tried to maintain a uniform depth while being tossed about by the current. Fins hit faces, different divers were swimming up and down at the same time, and we all breathed a sigh of relief when finally safe aboard the tenders. The relief evaporated quickly, though, when we realized we were short two divers. Following is an understated account of the ordeal that had transpired, provided for this report by Richard:

At dinner that night, we raised glasses to our friend whose dive turned from fun to decidedly not-fun in an the twinkling of an eye, and I believe we all uttered silent thanks to good luck or providence that we were all dining safely together. It was a sobering afternoon, but the best cure for a bad dive is a good one, so we made the short run back to AAII’s home port of Ambon Harbor, and kitted up in the gathering darkness. On this final night dive of the trip, I was again at the right place, at the right time when I heard one of our guides screaming gleefully into his regulator. This time the prize was a Flamboyant Cuttlefish hunting its way across the sandy bottom (the only known member of the cuttlefish family that moves in this manner). This astoundingly beautiful and rare cephalopod, a mere two inches long, produced the most amazing display of undulating and strobing bright colors along its back, likely meant to warn predators that it is quite poisonous to eat. Still photos of this creature can never completely do it justice because of the motion of colors, so we were very lucky to have a skilled videographer in our group who captured not only its outrageous color displays, but hunting behavior as well. You no doubt have been enjoying Mike Dunn’s (aka Kiddoc) fantastic work on video clips throughout this report, but this is my favorite:

Awaking back in snug and familiar Ambon Harbor, we enjoyed a hearty breakfast and set up for our final two dives of the trip. We were stuffed full to overflowing with the wonderful diving we had experienced during the last 8 days, but there was a sumptuous dessert yet in store for us. We were thrilled to see even more new and wonderful sights on the last dives, including juvenile Pinnate Batfish, Pegasus Sea Moths, various ribbon eels garbed in juvenile black, adolescent yellow, and adult royal blue, and Porcelain Crabs hiding safely in the poisonous tentacles of giant anemones and collecting bits of food by waving delicate filtering fans through the rich sea. But amazing Ambon saved perhaps her finest offering for the final dive. Less than a year ago, a totally new species of frogfish, aptly named the Ambon Frogfish, was discovered right here in these waters. After the luck we had experienced so far with finding many of the rarest and sought after creatures, we barely dared to hope for a sighting of this new fish, but once again our amazing guides came through, and soon we were admiring and photographing this splendidly strange-looking and beautiful fish. How could a dive trip end so perfectly?

With the diving over, we began the rinse-dry-pack dance and spent the afternoon on board winding down and relaxing, but a few of us wanted to have a closer look at Ambon City, and although some of the crew members advised us against it without explanation, we persuaded a couple of them to tender us in to the city. We docked in what could only be described as a squalid harbor, where rusting and obviously leaking boats seemed to be both the home and office for Ambon merchants and fishermen. Children played on the littered beach and swam in water floating with debris and displaying the prismatic surface sheen of suspended diesel fuel. Our group of seven wandered the town, sidestepping open gutters on the streets that seemed to contain raw sewage and deflecting the curious stares of townspeople, and eventually we stopped for a beer in a dark, muggy restaurant. As we sipped our brews and chatted about the trip, we decided that the crew of the AAII was likely more embarrassed about the general unpleasantness of Ambon City than concerned for our safety. And no time did we feel threatened or unsafe, just disquieted at the conditions of life and intense poverty. We hailed a taxi; in this case a micro van, and the 7 of us packed in like Vienna Sausages for a short ride up to a steep hillside restaurant overlooking the city. We snacked and had another round, and observed the city from above. From a distance, Ambon City is quite a lovely portside town, and, we realized, “from a distance” is really quite close enough. The sun was setting as we emptied the last of our beverages, so we crammed back in our hired van, and laughed as the music blared from distorted speakers, and said a prayer for unfailing brakes as our taxi careened down the steep, winding roads back to the harbor. Safely aboard our tender, albeit a little tipsy, we left the dock and motored into the now pitch-dark Ambon Harbor for our fifteen minute ride home. We glided past small fishing boats tending their nets, sitting motionless and illuminated with dim lanterns. Our thoughts were on dinner and flights home and such, when suddenly we felt an unsettling “thump” and one of the engines chugged to a stop, so we halted and tilted the motor to reveal the prop hopelessly damaged from hitting a submerged object. No worries, we have two engines, so we continued on with the remaining healthy engine, when moments later it fouled in one of the fishing nets and fell silent. We realized after a few minutes that the props could not be untangled or repaired without tools we didn’t have. In fact, there was quite a long list of things we didn’t have with us, including any sort of navigation light or flashlight. We were dead in the water, on a pitch-black moonless night, in or near a navigation lane for heavy marine shipping. Fortunately, our guides did have cell phones along, so they called the AAII and a crew was promptly dispatched on the other tender to retrieve our stranded and sheepish shore party. While we waited for rescue, we resorted to using illuminated cell phone screens and camera flashes to alert passing craft of our presence, and eventually to help the other tender find our otherwise completely dark vessel bobbing in a featureless sea. We boarded the AAII for the last time, with another tale to tell, and soon we were all enjoying our final meal on board. This time, the entire crew joined us for our farewell. Musical instruments were unlimbered and songs of the region were played and sung, while our now tight-knit group said goodbyes and spoke of constructing the immense report that you, hopefully, have enjoyed viewing as much as all of the contributors have enjoyed producing it. We talked about the amazing experience we had just shared, about the boat, about the diving, about the wonderful people on board who worked tirelessly for our pleasure and became our friends. And we also talked about how wonderful it would be to try to relive this matchless experience, to share the same waters on the same boat with the same friends, but we all know dreams like that never pan out in real life. But somehow, only a few months later, we miraculously managed to pay the ultimate tribute to our experience. We booked the AAII again, and in March 2010, we are all going back! And to those of you who might hope for another report of this size and scope after the next trip, I can only offer the advice all divers have burned in their brains: Don’t hold your breath. Archipelago Adventurer II Article Text © Michael Southard — January, 2009 REPORT DIRECTORY

REPORT LINKS

|